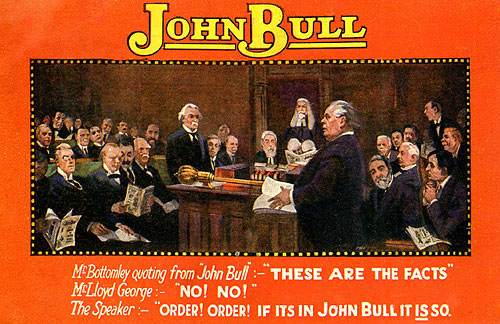

Horatio Bottomley was the founder and editor of John Bull, one of the most popular magazines of the 20th century. This postcard promoting the magazine portrays Bottomley as an MP putting the prime minister Lloyd George in his place.

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until Robert Maxwell did the media, in that case the Daily Mirror, help create such a monster.

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until Robert Maxwell did the media, in that case the Daily Mirror, help create such a monster.

Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times but used it to promote his projects. He came to note in the courts in 1893 when he was able to defend his printing and publishing company, the Hansard Union, from bankruptcy and the fact that £100,000 had gone missing. In 1900, he failed to win election as an MP but won £1,000 in a libel case after he was described as a fraudulent company promoter and share pusher during the campaign. The Financial Times included him in a supplement titled ‘Men of Millions’.

Bottomley’s reputation in the courts dissuaded others from taking legal action – a strategy all used by the likes of Maxwell, known as the ‘Bouncing Czech’ in Private Eye. Maxwell even published a one-off magazine backed by himself and other enemies of Private Eye, Not Private Eye, after he won a court case against the magazine’s campaigns. Bottomley survived other cases against him but his taste for champagne and race horses led to him becoming bankrupt in 1912 and so he was forced out of parliament.

In 1906, Bottomley had founded John Bull with the help of Julius Elias (later Lord Southwell), managing director of the printers Odhams. The magazine, with its belligerent stance, championing of the common man and prize competitions – including Bullets, which was akin to coming up with cryptic crossword clues – became incredibly successful once the war started. He tried to launch a women’s version, Mrs Bull, in 1910, though this was short-lived.

This John Bull cover from 1917 is a good example of Bottomley’s self-promotion

Such was Bottomley’s popularity in wartime that he was despatched by David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill as an unofficial emissary, and persuaded shipwrights on the Clyde not to go on strike. He toured the country to help recruitment and his visit to the western front was widely reported in the press. The Evening News even ran a poster saying ‘Bottomley Wanted’ to promote a story calling for him to join the cabinet and attacking the government after Haig’s offensive on the Somme failed. Such was the power of the press that Lord Northcliffe was appointed director of propaganda, his brother Lord Rothermere became air minister, and Daily Express owner Sir Max Aitken served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and as minister for information (and in 1916 became Lord Beaverbrook). However, Bottomley never made it into government.

He was lauded in the music halls, with a 1915 song ‘Mr Bottomley – John Bull’ by Mark Sheridan.

According to the historian Niall Ferguson, ‘Horatio Bottomley’s John Bull was selling as many as two million copies by the end of the war, a figure beaten only by the new Sunday Pictorial [for which Bottomley also wrote a column for £150 a week, a massive sum that had to be personally approved by Lord Rothermere] and the News of the World.’

John Bull led to a cause célèbre in the film world when it accused the makers of what was intended to be an epic feature, The Life Story of David Lloyd George, of being German sympathisers. The Ideal Film Company sued John Bull and won the case in January 1919. Yet the film was never released, because the prints were bought – for £20,000 – by parties acting for Lloyd George. It was lost until 1994 when it was found at the home of Lord Tenby (Lloyd George’s grandson).

Victory souvenir from John Bull made of metal from a German U-boat

The magazine also bought the Deutschland, a U-boat handed over by the Germans as part of the Armistice, and sailed it around Britain. It was broken up in Birkenhead in 1921 and the magazine sold badges that were: ‘Guaranteed to be made from metal forming part of the ex-German submarine Deutschland.’

In 1920, Beverley Nichols invited Bottomley to speak at the Oxford Union in support of a motion in favour of independent political parties. (Nichols became a popular writer and would go on to write a weekly column for Woman’s Own from 1946 to 1967). He described Bottomley in his book, 25:

A grotesque figure. Short and uncommonly broad, he looked almost gigantic in his thick fur coat. Lack-lustre eyes, heavily pouched, glared from a square, sallow face … It was not till he began to talk that the colour mottled his cheeks and the heavy hues on his face were lightened …

Bottomley won the motion, and Nichols records another aspect of the arrogance of the man – he was disappointed that he had not broken the record for the numbers in the audience at such debates. For breakfast next morning, he ordered, ‘A couple of kippers and a nice brandy and soda.’

Bottomley’s Victory Bond Club advertised in John Bull in 1919

With the end of war, Bottomley won a seat in the general election as an independent MP for Hackney South. However, the swindling of his Victory Bond Club, which was heavily promoted in John Bull, was coming to light. Another magazine, Truth, warned its readers off the scheme and Bottomley issued several writs against it, which the magazine ignored. Bottomley also threatened wholesale newspaper distributors – a tactic John Major, the Conservative prime minister, used in 1993 to prevent distribution of the New Statesman when it carried an article about a supposed affair (in 2002, Major admitted having had a four-year affair with the former Conservative minister Edwina Currie from 1984). Reuben Bigland, a printer who had been slighted by Bottomley, had tracked his activities for years and his pamphlet ‘The downfall of Horatio Bottomley: His latest and greatest swindle’ prompted the MP to sue him for criminal libel and blackmail in October 1921. He lost and, along with Odhams, was fined £1000. Bottomley tried again on the blackmail charge, and lost again.

The country turned against him, with the Times thundering out, and Bottomley was committed for trial at the Old Bailey. The Illustrated London News reported his trial, with the verdict being its front-page illustration (3 June 1922). Bottomley was sentenced to 7 years. Mr Justice Salter said:

You have been rightly been convicted by the jury of this long series of heartless frauds. These poor people trusted you and you have robbed them of £150,000 in ten months. The crime is aggravated by your high position.

Illustrated Evening News reports Bottomley’s guilty verdict in 1922

The report made reference to the Sword of Justice seen hanging on the courtroom wall. Bottomley had earlier told the jury that it would drop from its scabbard if he was found guilty: it did not fall.

Travers Humphreys, the prosecuting barrister, had lost a John Bull lottery prosecution to Bottomley in 1914 but succeeded this time. He wrote in his memoirs:

[In 1914] he was a brilliant advocate and a clever lawyer, though completely unscrupulous in his methods … In truth, it was not I who floored Bottomley, it was Drink. The man I met in 1922 was a drink-sodden creature whose brain could only be got to work by repeated doses of champagne.

In prison, he was recognised and seems to have been popular with many inmates because of John Bull‘s tradition of backing the working man and sending parcels to prisoners of war. A story is told that a padre came to visit and found the prisoner stitching mail bags:

Ah, Bottomley, sewing?

No, padre, reaping!

After prison, Bottomley portrayed his experiences in the manner of Oscar Wilde, with a poem ‘A Ballad of Maidstone Gaol’ by ‘Convict 13’ (his prison number). He also published a book, Songs of the Cell (1928), and toured the music halls. However, he was a sad sight in his later days and died on stage at the Windmill theatre in 1932. His ashes were scattered near his house, The Dicker, in Upper Dicker, near Eastbourne.

As for John Bull, sales plummeted from something like 1m-2m to 300,000 in 1922, but Odhams was able to pull it round as a serious and responsible paper. Within a year it was back selling a million copies a week. After world war two, John Bull relaunched itself with colour, illustrated covers and a focus on fiction from writers such as Agatha Christie and Nevil Shute. However, with the advent of commercial television, its sales fell, like all the general interest weeklies, and it was relaunched in 1960 as Today. In this format, it survived until 1964, but it was a slow death for all the popular weeklies and it was taken over by Weekend.

Sources

The Rise and Fall of Horatio Bottomley: The biography of a swindler by Alan Hyman, Cassell, 1972 (well indexed)

Horatio Bottomley by Julian Symons, House of Stratus, 2001 (no index)

‘How the papers went to war’, by Niall Ferguson, 27 October 1998, Independent, p15

‘General weekly magazines’, Magforum.com. John Bull

To see almost 500 magazine covers and pages, look out for my book, A History of British Magazine Design, from the Victoria & Albert Museum, the world’s leading museum of art and design

To see almost 500 magazine covers and pages, look out for my book, A History of British Magazine Design, from the Victoria & Albert Museum, the world’s leading museum of art and design

To see almost 500 magazine covers and pages, look out for my book, A History of British Magazine Design, from the Victoria & Albert Museum, the world’s leading museum of art and design

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until