Here are 10 things that might not exist without magazines.

1. The word ‘magazine’

The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1731

In January 1731, the Gentleman’s Magazine was the first publication to use the word ‘magazine’ in its modern sense as a periodical.

Before Edward Cave, its publisher, came up with the title, most periodicals were called journals and a magazine was a storehouse, from an ancient Arabic word. That sense still exists, in the sense of a gunpowder magazine, or a magazine of bullets for a machine gun.

But Cave didn’t just come up with the word, his collections of news, opinion and articles set the approach for the modern magazine, and it was published for almost two centuries.

Samuel Johnson listed the word in his dictionary of 1755: ‘Of late this word has signified a miscellaneous pamphlet, from a periodical miscellany named the Gentleman’s Magazine, by Edward Cave [who used the pen-name Sylvanus Urban].’

2. Charles Dickens

Dickens’ Household Words

The quintessential Victorian author followed in his father’s footsteps as a journalist and worked on a variety of publications for eight years from 1829. He then became editor of Bentley’s Miscellany, which published Oliver Twist in twenty-four monthly instalments from February 1837. In 1840, he launched his own magazine, Master Humphrey’s Clock in which was published The Old Curiosity Shop. Most of Dickens’ works were first published in magazines as weekly instalments. The publishers then collated them as monthly parts or whole books. His first novel, The Pickwick Papers, was published in 19 issues over 20 months from 1836.

This publishing approach affected his writing style – it was vital for readers to remember his plots and characters from week to week, so encouraging vivid characterisations and descriptions in his works.

Dickens went on to launch Household Words, which was published by Bradbury & Evans on Fleet Street from 1850. This was followed by All the Year Round in 1859, which carried on after his death in 1870 under the editorship of his son, Charley, for another 18 years. The Dickens Fellowship in tribute to the writer was founded in London in 1902.

3. The curate’s egg

The first issue of Punch magazine dated 17 July 1841

The English expression ‘a curate’s egg’ describes something of mixed character (good and bad).

The phrase was coined in the caption of an 1895 Punch cartoon entitled ‘True humility’ by George du Maurier. This showed a curate who, having been given a stale egg by his host but being too meek to protest, stated that ‘parts of it’ were ‘excellent’ (9 November, p222).

Punch has been credited with coining or popularising many words and expressions. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the magazine almost 4,000 times in its entries, from ‘1984’ to ‘intersexual’ to ‘youthquake’ to ‘zone’.

4. The Pre-Raphaelites

Portrait by Millais of Effie Gray holding a copy of Cornhill magazine (Perth museum)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848 as a secret society, with its founding members, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, all signing their paintings as PRB.

That strategy changed two years later when the Pre-Raphaelites launched a magazine – The Germ – to promote their cause. Rossetti was the editor and the literary monthly was wrapped in a yellow cover.

The January 1850 issue included engravings by William Holman Hunt to illustrate the poems ‘My Beautiful Lady’ and ‘Of My Lady in Death’ by Thomas Woolner. The Pre-Raphaelites’ work was at first regarded as scandalous, but by 1860 they had taken the art world by storm. Their illustrations appeared in many magazines, particularly Cornhill Magazine from its first issue. Millais painted his wife, Effie Gray, holding a copy of the magazine.

5. Mrs Beeton

A spread on puddings from Mrs Beeton’s book

Isabella Beaton was the wife of Samuel Beeton, who bought the Victorian world magazines such as The Queen and the Boy’s Own Paper. Isabella was a vital part of Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, which was one of the first magazines to address the expanding market of middle-class woman who did much of her own housework. Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management was spun out of Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. Isabella was just 25 when the book came out, but she died four years later giving birth to their fourth child. Samuel’s life fell apart after that and he lost control of his publishing empire.

6. The Daily Mail

This logo from the Daily Mail echoes the original masthead for Answers Magazine

The editorial strategy developed from 1881 by George Newnes with Tit-Bits – editing down news and facts to their essence and presenting them as entertainment – influenced Alfred Harmsworth as he established both his rival magazine, Answers, and the ‘tabloid’ news style of the Daily Mail (launched in 1896).

Harmsworth’s move from magazines into newspapers (the Daily Mirror followed in 1903) was echoed by Pearson’s Weekly magazine publisher C. Arthur Pearson, who started the Daily Express (1900). These three stalwarts of British newspapers are still published today.

7. Cryptic crosswords

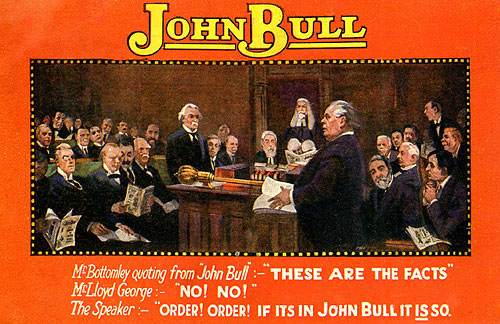

John Bull’s Dictionary of Bullets

Cryptic word games were popular as puzzles in British magazines from the Victorian era. My pet theory is that the ‘Bullets’ prize puzzles in the weekly John Bull – the best-selling magazine from about 1910 to 1930 – created a nation of cryptic thinkers.

It’s difficult to make sense of many Bullets today because of the way they drew on topical events of the times. However, Bulleteer Bill’s blog is based on cuttings left over from his dad’s obsession with the game (an obsession shared by Alan Bennett’s father).He explains ‘The basic premise was that the competition setters would supply a word or a phrase which the player had then to “complete” or add to in a witty, apposite way’ and quotes the following examples:

A HUNDRED YEARS HENCE: More Radio – Less Activity? (In 1949 when BBC Radio was a fixture in the country’s homes and talk was of expansion and more stations.)

ALL DAD THINKS OF: Retrieving fortunes at Dogs! (Greyhound racing was a popular pastime with dog tracks in most towns, and there’s the extra pun on ‘retriever’.)

Once crosswords were established in Britain in the 1920s – in magazines such as Answers before newspapers such as the Times and Telegraph – it was only natural to combine ‘Bullets thinking’ with crossword clues.

To mark the 1,000th competition, John Bull published a Dictionary of Bullets in 1935.

8. St Trinian’s

Searle’s St Trinian’s on a 1949 Lilliput cover

The first of Ronald Searle’s St Trinian’s cartoons about a bunch of anarchic schoolgirls was published in Lilliput and he did several covers for the magazine, the first in December 1949, before he established himself on Punch.

Not only that, Kaye Webb, Searle’s first wife, was the picture editor of Lilliput.

The popularity of the cartoons led to four films between 1954 and 1966. The first was The Belles of St. Trinian’s with Alistair Sim, Joyce Grenfell and George Cole.

Another film followed in 1980, and then two films in 2007 and 2009 with Rupert Everett playing two roles, one of the girls and the school’s spinster headmistress.

9. ‘Metal Postcard’ by Siouxsie and the Banshees

A Heartfield montage on the cover of Picture Post dated 9 September 1939

In the 1930s and early 1940s, Stefan Lorant published the photomontages of German Dadaist John Heartfield. Both had fled to Britain to escape the Nazi regime. Lorant popularised Heartfield’s anti-Hitler photomontages in Britain through both Lilliput and Picture Post – two of the most popular magazines of the era.

Heartfield’s response to the Munich Agreement, ‘The Happy Elephants’ of two elephants flying, was used in the third issue of Picture Post (15 October 1938) and his montage of Hitler as the Kaiser used as a front cover for 9 September 1939, a week after war broke out. The images became familiar to the British population and one of Heartfield’s montages, ‘Hurray, the Butter is All Gone!’ inspired the song ‘Metal Postcard’ by Siouxsie and the Banshees.

10. £100m for Britain’s poorest people

The Big Issue of 4 March 2016 celebrates 200 million sales

In 1991, John Bird founded The Big Issue to help homeless people earn some cash and to try to shame the John Major government into doing more to help them. In April 2016, The Big Issue marked the sale of 200 million copies.

Street vendors sell 100,000 copies a week and the proceeds they earn help keep a roof over their heads.

In total, Bird reckons the magazine has helped homeless people earn £100m. Furthermore, The Big Issue has inspired street papers in 120 other countries, leading a global self-help revolution.

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until

Other members of Lloyd George’s cabinet are shown consulting their copies of the magazine, including Winston Churchill. Bottomley was founding chairman of the Financial Times and twice a member of parliament – but also one of Britain’s biggest fraudsters. The magazine was the medium by which he promoted himself and his dodgy schemes, and not until

To see almost 500 magazine covers and pages, look out for my book,

To see almost 500 magazine covers and pages, look out for my book,